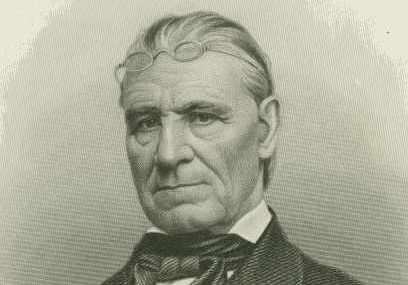

Wendy Knickerbocker, Bard of Bethel: The Life and Times of Boston’s Father Taylor 1793-1871, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

The history of maritime ministry’s institutions and individuals illuminates its modern iterations around the world. Knickerbocker, who retired from the Maine Merchant Academy library and studies American religious and cultural history in New England, offers a striking portrait of an early, pivotal figure in seafarers’ welfare in North America.

Taylor foreshadowed the ecumenical impulses and emphasis on practical assistance that came to characterize most seafarers’ welfare organizations in the latter nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Raised in Virginia and orphaned as a child, Taylor ran away to sea at the remarkably young age of 7. The combination of growing up on the sea and the lack of opportunity for formal education was portentous, and proved key to Taylor’s ability to relate to mariners in simple and straightforward ways throughout his life.

When Taylor came ashore he was soon attracted to the passion of Methodism, a recent movement that favored simple, direct preaching, less formal worship, and a down-to-earth blending of piety and care for the poor. From its roots in the work of John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield in eighteenth-century Britain, it became one of the major American denominations by the end of the nineteenth century. For the first decade of his ministry Taylor was an itinerant preacher among the Methodists of New England, teaching himself to read the text of Scripture.

Taylor’s simple, passionate preaching was peppered with sea analogies and stories. His abilities caught the attention of the Boston Port Society, a group of Boston Methodists and Unitarians that wished to provide moral and practical support to seafarers in the port. Taylor was employed by the Port Society in 1829 to be the pastor of its non-denominational Seamen’s Bethel Church, a post he would hold until his death in 1871. The Boston Port Society also created the Seaman’s Aid Society and ran various programs, including Mariner’s House, a boarding house for seafarers. (Mariner’s House still operates today; the Seamen’s Bethel Church building is still across North Square, though now is Sacred Heart Catholic Church). Taylor also contributed to the founding of the Seamen’s Bethel chapel in New Bedford,and likely provided at least some inspiration for Herman Melville’s Father Mapple at the Whaleman’s Chapel of Moby Dick fame.

Taylor enjoyed great success from his extraordinary public speaking abilities. Notable nineteenth-century writers and preachers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Dickens, and Charles Spurgeon were amazed by Taylor’s ability to inspire audiences. He evidenced an intuitive grasp of how to keep listeners deeply engaged, even on the edge of their seats despite his own lack of formal education in religion or rhetoric. Knickerbocker notes that those who wished to take notes on Taylor’s sermons sometimes gave up, a result of either their own inability to follow Taylor’s train of thought or of being carried away by Taylor’s eloquence. The Virginian ended up as one of his generation’s best-known preachers. In particular, like many other social reformers of his time, his fight against the abuse of alcohol occupied Taylor’s most productive years and that was the target of his most fiery rhetoric. Taylor additionally looked toward the many all-too-real stories of the other dangers of life in port, including lousy seamen’s hotels and crimpers, for topics of sermons and exhortations to repentance and personal reform.

Knickerbocker writes that “Taylor’s personal magnetism infused and directed all of his missionary efforts.” (205) This ability exerted a multiplied effect on seafarers’ welfare in Boston. Events featuring preaching and other public speaking were lucrative fundraising opportunities for the Bethel and the Port Society.

Taylor was also remarkable for his willingness to work with others outside his Methodist denomination, including lifelong partnerships with Unitarians and Free Masons. In both these groups he seems to have found refreshing the emphasis on practical assistance to those in distress and avoidance of divisive doctrinal points, making Taylor a forerunner of modern maritime ministry in yet another way.

Knickerbocker’s biography also brings out Taylor’s family life and something of his private character. He seemed to love being around people and displayed great wit and empathy. For all his effort at self-education and impassioned preaching, Taylor was not a great reader or theologian. He claimed that that every time he picked up a book, someone would ring at the door and the conversation would distract him.

Knickerbocker’s biography is well-written and edited. It uses an extensive range of resources, bringing clarity and balance to earlier biographies. It is a great read, sympathetic to Taylor and his cause, but still realist in its assessments. It should be inspiring and instructive for anyone involved in maritime ministry in North America in our time.

Review by Jason Zuidema