This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Leïla Choukroune and Elisabeth Mavropoulou

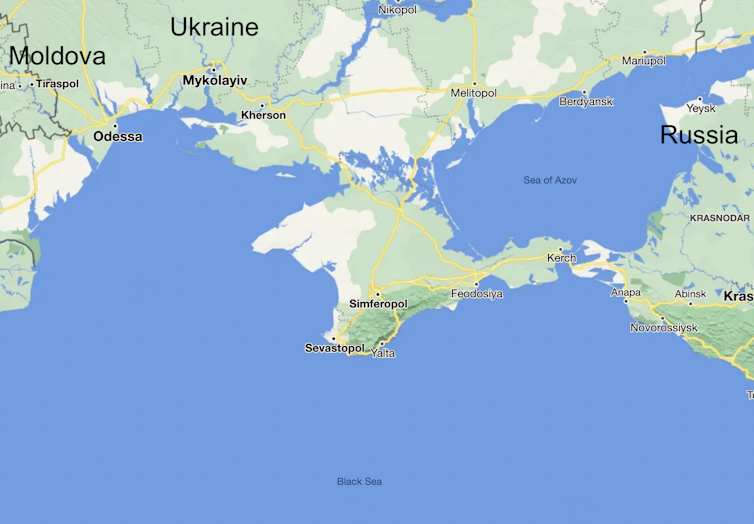

While the world’s eyes have been on civilian casualties, forced displacement and potential war crimes on Ukrainian land, the plight of hundreds of seafarers trapped in commercial ships for the past several months has gone mostly unnoticed. They have been stranded in the main Ukrainian ports of Mariupol, Kherson and Odesa, unable to escape by land but unable to move by sea either for fear of Russian mines and military attacks.

It’s difficult to ascertain exact numbers in such a chaotic situation, but according to reports that we have received in the past couple of days from the International Chamber of Shipping, around 500 mostly Ukrainian seafarers are still stranded. Some 1,500 more of multiple nationalities are said to have managed to escape over land through Romania and Moldova since March. Some fled along with many Ukrainians, while others were eventually repatriated with the help of their ship owners and embassies.

Around 140 commercial ships have been marooned in Ukrainian territory in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov since the war broke out, effectively trapped between blockades and sea mines. When the NGO Human Rights at Sea (which Elisabeth works for) visited Odesa in late March, it found that provisions on many vessels were running low, including medical supplies and drinking water.

On a visit to one ship, the team found that engines were only being started two hours a day to provide heating and hot water, but otherwise they were freezing. Some crews had been working 20-hour days to keep vessels ready to set sail, though this looks impossible for the foreseeable future.

The International Maritime Organization, which is the UN agency responsible for shipping safety and security, has sought to work with Russia, Ukraine and other relevant states to establish a blue safe maritime corridor to allow seafarers and ships to evacuate by water. This has been complicated by mines in the water that need to be neutralised first, which could take months of negotiation. During April, the Russians have also devoted more attention to attacking Ukrainian ports, while some merchant ships have been the subject of indiscriminate attacks.

A complex legal environment

To protect seafarers, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has in recent years adopted numerous international legal conventions covering all aspects of seafarers’ lives, including working hours, pay, leave, safety, repatriation and identity documents. This includes the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), which is the reference instrument for the industry.

Even so, it remains extremely difficult for seafarers to enforce their rights as it depends on who qualifies as the “competent authority” that has a duty to provide them. This is complex because there are many moving parts, such as the owner of the ship, management, flag, territorial waters, port, labour contract and nationality of the seafarer. This makes enforcement of the law against the responsible party difficult, creating an environment of impunity and making it difficult to hold anyone accountable when seafarers are denied their rights.

During the pandemic in 2021, some 300,000 men and women were stranded at sea because government restrictions prevented them from going ashore. Some had been working at sea for over 17 months, despite an MLC maximum of 11 months without a period onshore. Amid alarming reports of labour conditions, the ILO, UN and various other bodies launched a set of voluntary guidelines to try and further protect seafarers’ human rights. Despite this collective effort, there is still not enough transparency in reporting infringements of seafarers’ rights, and accountability within the wider industry continues to fall short.

So what does all this mean for the seafarers stuck in Ukrainian waters? For one thing, various human rights are being infringed, including the right to life, the right not to be subject to inhuman and degrading treatment, the right to liberty and the right to an effective remedy.

The armed conflict also triggers the application of international humanitarian law, which is essentially the laws of war. Just like the many accusations about Russian activities on land, the fact that ships have been attacked amounts to targeting of civilians and civilian objects, which constitutes a war crime.

In support of such an argument, the laws of naval warfare also explicitly prohibit attacks against merchant vessels flying a neutral flag, while the fact that Russian warships have, at times, reportedly blocked ships from leaving or entering Ukrainian ports effectively amounts to a naval blockade.

War crimes against seafarers and merchant ships should therefore be included in any future attempt to bring Vladimir Putin to justice at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. Though international law recognises a proportionality principle of targeting, where civilian casualties can be justified when there is a concrete and direct military advantage anticipated, it is highly unlikely that any attack against these ships and the crew could be justified in this way.

The difficulties that seafarers are facing in Ukraine further highlights the vulnerability of these workers in the global economic system. It is not only them but commercial shipping and trade that are under attack here. With 90% of world trade conducted via maritime or river transportation, seafarers are essential to our daily lives. The fact that they receive such limited protection and so little media coverage during crises is a major problem.

In the short term, it is vital that all stranded seafarers are evacuated through humanitarian land corridors so that they can return home. Once the conflict is over, if the Russians are held legally accountable for their actions towards seafarers in this conflict, it would send a message that the time has finally come to take the rights of these workers more seriously. In the efforts by Ukraine’s chief prosecutor to gather evidence on war crimes within the country, Russia’s actions in Ukrainian territorial waters therefore need to be included.

Authors

- Leïla Choukroune is Professor of International Law and Director of the University Research and Innovation Theme in Democratic Citizenship, University of Portsmouth

- Elisabeth Mavropoulou is Lecturer in International Law, University of Westminster

Image: SCI Flickr